DEA Drug Scheduling: How Drug Policies Shaped the Opioid Crisis

News headlines punctuate the impact of the opiate crisis in America on a daily basis – detailing people dying, fam…

News headlines punctuate the impact of the opiate crisis in America on a daily basis – detailing people dying, fam…

Protecting our first responder populations is essential to maintaining national security, social well-being, and citizen…

As a Latina, I’ve witnessed firsthand how drug addiction has quietly made its way into the lives of individuals an…

Sleep is supposed to be a state of healing to eventually wake up with a fresh start. However, the scary reality of sleep…

At XFoundation, we’re always looking for new ways to keep our communities safe and informed. When we started thi…

There is a lack of information regarding the relationship between fentanyl and culture, although there are evident assoc…

Imagine getting the phone call that everyone dreads, a loved one has passed away. For parents, such news is a nightmare,…

Beyond Overdose 2025 recap On March 18, XFoundation hosted “Beyond Overdose: Addressing the Risk of Fentanyl Poiso…

.jpg?resize=410x0)

Introduction: A Growing Crisis Adolescence is a time of growth and exploration but also of vulnerability. Among the many…

Scholar's Corner

Attending college is often seen as a milestone, offering the promise of independence and opportunity. Students across th…

Scholar's Corner

As Halloween approaches, it's not just ghosts and goblins we need to be wary of. With the rising threat of fentanyl maki…

Scholar's Corner

If I were to ask you, “How does addiction start?” What would be your answer? Many people do not understand h…

Article

The Gerchow and DeVivo family’s profound loss of Xavier to fentanyl poisoning was a heart-wrenching event that lef…

Scholar's Corner

The opioid epidemic continues to plague communities, with youth increasingly at risk. In the US, the child and adolescen…

Scholar's Corner

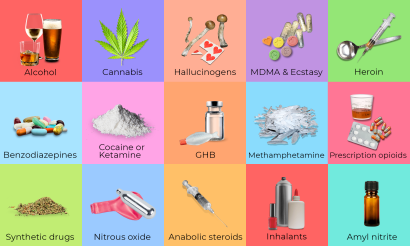

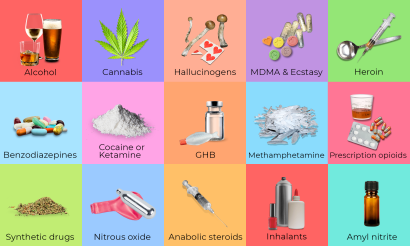

Fentanyl Facts for Teens: In today's culture, it is not uncommon site to see or hear of teenagers regularly engaging in…

Article

It’s spring break for my school district, a much-needed week off for everyone. When we come back from break, boys&…

Scholar's Corner

“O le tele o lima e mama ai se avega”

“E so’o le fau i le fau”

“E le tu f…

Article

"My Dearest Xavier,

In grief, countless emotions and feelings are coursing through the body at once. Som…

Article

The opioid crisis is a pervasive issue, and today, fentanyl is one of the most potent and dangerous contributors to the…

Newsletter Article

Hello XFamily, As we welcome the New Year, we want to personally thank you for supporting XFoundation and helping us rai…